I prefer to be alone, but next to someone…

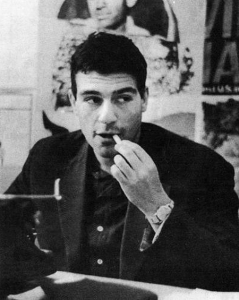

These are the words that first caught my attention while I was browsing for new, must-read books in a Yerevan bookstore. They were the words of the celebrated Soviet writer, Sergey Dovlatov. I briefly looked through some of his books and definitely decided to buy them.

I had heard of Dovlatov before, but never had the chance to read his works. After discovering his writings, he quickly became one of my favorite authors. Most Armenians like Dovlatov because of his partial Armenian origin. He was the son of a Jewish theater director Donat Mechik and an Armenian editor and proofreader Nora Dovlatova.

However, it was not his Armenian background that made me fall in love with Dovlatov once and for all. It was his style of writing, sense of humor, sarcasm and cynicism that really captured me. The writer had a great talent for conveying the true reality of Soviet times, complete with its faults, deceptions, narrow-minded chinovniki (bureaucrats), false and ridiculous party slogans, etc.

On the other hand, he was never overly-negative. Dovlatov’s unique sense of humor allowed him to avoid this. Every difficult and sad situation was mixed with some humor, irony, and sarcasm.

“I have ceased to divide people into positive and negative. And the literary heroes – even more so. Also, I’m not sure that in life, crime is inevitably followed by repentance, and achievement is followed by bliss. We are what we feel.” (The Compromise (Компромисс) — New York: Knopf, 1981)

This is one of the writer’s most important philosophical approaches to life. An individual in a given Dovlatov work may seem like a negative character, but when you carefully analyze this person, you will not find a real evil. Every person lives his/her life in his/her way and does not harm others. That is what makes Dovlatov’s works positive overall.

I read once that Dovlatov had a very interesting principle – to start every word in every sentence with a different letter. This is definitely the case with his writings. If one reads his works, he or she will find that he truly follows this principle.

His novels are semi-autobiographical. Almost every story is a situation that happened to him and his friends and colleagues. Therefore, it is easy to know Dovlatov’s nature and personality just by reading his works. He was a very tall and big man who was shy about his appearance as a child and who later grew up to become a handsome ladies’ man. He almost always wrote about his life, including his career, military service, family, etc.

Early life in the USSR

This year Dovlatov would have been 74. He was born in Ufa in the midst of the evacuation during the Great Patriotic War. After three years, he and his family returned to Leningrad (St. Petersburg). Dovlatov’s mother brought up her son by herself, due to the fact that the father, Donat Mechik, soon left them. Sergey grew up as a smart and well-read boy with exemplary behavior.

After graduating from the school he was admitted to the philological faculty of the Leningrad State University. However, after two years he was expelled from the university for regularly missing lectures and for poor academic progress. Right after he was dismissed from classes, Dovlatov was drafted into the army and served for three years in the system of corrective labor camps. “The world in which I appeared was terrible,” he once said. He wrote much about the experience of his tough army life. (The March of the Single People (Марш одиноких)).

After returning from the army, Dovlatov decided to try journalism. He was admitted into the faculty of journalism at Leningrad State University. His financial status was quite poor and he had to find work elsewhere. So, Dovlatov started his journalistic career in one of the local newspapers. He got acquainted with famous litterateurs and poets of Leningrad, such as Rein, Neiman, Wolf, Brodsky, etc.

Soon, Dovlatov left his city. In search of a new job, he suddenly moved to Tallinn, the capital of Soviet Estonia. There, he worked as a correspondent at the local newspapers “Soviet Estonia” and “Evening Tallinn”. Dovlatov was a successful journalist and the editor Turonok liked his articles. Estonian colleagues often said that Dovlatov was able to make “any nonsense into brilliant writing.”

The only problem for the chief editor was that Dovlatov drank too much. In fact, he almost always appeared in the editorial office drunk, so much that they could not depend on him for serious reports. Though the editorial staff highly appreciated Dovlatov’s talent as an analyst, writer, and journalist, Dovlatov needed to leave his job and Estonia. He could not live there without an apartment, friends, and family. Further, the KGB blocked his attempts to publish one of his collections of short stories.

Dovlatov returned to Leningrad and started work at another newspaper. Again, he tried to publish his stories but magazines refused to publish them. Dovlatov’s stories therefore appeared in the “samizdat,” the underground dissident Soviet literature. He also began to get published in abroad, in émigré journals. This was the reason for Dovlatov’s expulsion from the Soviet Journalists Union. For a period, he went to Mikhailovskoe in the Pskov area to work as a tour guide in Pushkin’s Reserve (Pushkin Hills). His time at Pushkin Hills later served as an inspiration for his novel “The Reserve” (Заповедник).

This was a very difficult time in Dovlatov’s life. In fact, it was perhaps the worst period. His wife, Yelena, had decided to emigrate to the United States with their little daughter Katya. Though Dovlatov was divorced from her, he nevertheless found it difficult to grasp that his family was leaving him. Yelena herself did not know what to expect from that uncertain journey and vague future in a distant, foreign country. However, she was sure that it was the best choice. Dovlatov could not stop her and hoped to meet them again. He knew that sooner or later he would follow them. At the same time, he deeply loved his country and did not want to leave it.

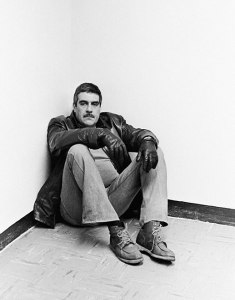

Dovlatov in New York (http://sergeidovlatov.com)

He stayed with his mother and their dog, Glasha. “Year by year, she [Glasha] becomes more and more human,” Dovlatov once said. “In fact, when she is around, I’m embarrassed to take off my clothes!” Meanwhile, he was still unable to publish any of his works. The authorities kept a close eye on him. He lost his work and began to drink more and more. The situation was critical and he faced a stark and difficult choice: either to stay in his native motherland, the Soviet Union, and remain an outcast and unappreciated writer, or to defect and emigrate to the West. In the end, he chose the latter.

Life in the USA

Dovlatov’s emigration started in 1978 from a transit country – Austria. He and his mother Nora lived for some weeks in Vienna and it was here where Dovlatov wrote a series of admirable stories which were successfully published in the US in “Continent” and other publications. Contrary to his expectations, fortune arrived to the writer in emigration. His stories began to be published in local journals for émigrés.

Before coming to the United States, Dovlatov was overcome by anxiety. On the one hand, he did not like the idea of leaving the USSR, his friends, and the hope to one day get published in his homeland. On the other hand, he was being constantly watched, not only by the police but also by the KGB. There were new challenges too, such as learning a foreign language, meeting different people, getting adjusted to a completely new culture, etc. To Dovlatov, all of this seemed so overwhelming.

Despite his negative expectations, Dovlatov soon became the head editor of the Russian-language journal The New American. This obviously was the brightest period of Dovlatov’s life as his journalistic activity was affirmed and he quickly became one of the most appreciated and successful émigré Russian-language writers.

“All the best hope was associated with this newspaper because it was so different from Soviet as well as émigré journalism. It was full of fresh ideas and stylistic elegance,” recalled Yelena Dovlatova.

Dovlatov with Russian poet, Joseph Brodsky, at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. (http://sergeidovlatov.com)

Unfortunately, The New American lasted only two and a half years. This was because, in Dovlatov’s words “it was made by brilliant writers but lousy financiers.”

At the same time, Dovlatov was also hired as a host for Radio Free Europe. Twelve books by him were published one after another in the US and Europe from 1978 to 1990. Dovlatov was even fortunate enough to get published in the very prestigious American newspaper The New Yorker.

For Dovlatov, it seemed as if all the troubles of the gray past were over and that his new life in New York would bring new bright color into his and his family’s life. Dovlatov no longer had to worry about being pursued by the KGB. He cut down on drinking. His books were successful. Further, his family was replenished by the birth of Dovlatov’s son, Kolya, in 1984.

However, Dovlatov’s depression, strangely, was deepening day by day. According to him, this was a “depression of causeless melancholy, powerlessness and disgust for life… Just all my life I was waiting for something: a matriculation certificate, the loss of virginity, marriage, a child, the first book, minimal money, and now all of these things have happened and there is nothing more to wait for. There is no source of joy.”

Actually, it was the depression of an unappreciated and unknown writer for his native readers. Dovlatov loved his homeland, the USSR, and his dear native city, Leningrad. Life in America was not the life for him. “Two things somehow brighten my life,” he wrote, “a good relationship at home and a hope to someday return to Leningrad.”

Dovlatov died in 1990 from a heart attack at the age of 49. He was buried in the Armenian part of the cemetery “Mount Hebron” in New York. It was too early for such a gifted writer to die. The USSR was just opening up under perestroika and the world had only just discovered the writer’s talent. Unfortunately for the world, his passing was untimely. However, his works and writings continue to live on and will be cherished by many for years to come.